Falklands War Remembered

Former Royal Marine Graham Cann searches for the missing pieces of the puzzle

As the 40th anniversary of the Falklands War approached in 2022, Graham Cann began tentatively thinking about revisiting the south Atlantic islands for the first time since he saw active service in 1982..

It wasn't, however, until he met Kim Casey, sister of the first British forces casualty Ben Casey, after reading about her loss in his local newspaper, that he took her advice and returned to the place he’d only known as a teenager.

It was poignant journey of discovery and the start of an extraordinary and life-affirming bond between the two.

On 2 April 2024, it was 42 years since the conflict started. Graham, 61, recalls his trip back to the Falkland Islands and surviving the notorious perils of San Carlos Water.

In January, Graham undertook a near 16,000-mile round trip to discover the missing pieces of a puzzle.

Accompanied by wife Jane, he spent eight days on the Falkland Islands, retracing his steps to try and make sense of his experiences as a 19-year-old supporting Commando Logistics Regiment. There were so many aspects he didn’t know, couldn’t remember and frankly, blocked out.

He paid his respects to the fallen, met other veterans and importantly, made an eight-mile ‘yomp’ from a mountain ridge called Two Sisters into the capital Stanley. It was done in memory Section Corporal Ian ‘Frank’ Spencer and seven other fallen comrades from his former unit 45 Commando, and who were killed in a battle of the same name.

Graham may have long ditched his kit bag but has carried a heavy burden of guilt for over four decades. Because he survived, yet 255 didn’t. He got married, had a daughter and went on to have a successful career on civvy street. Others didn’t get that chance.

He never spoke to Jane about what he went through during the conflict. He shut out his feelings and got on with life. A couple of years ago, however, as the 40th commemorations approached, he started to reflect on those frantic days in the summer of 1982.

Graham, wife Jane and Kim Casey. Photo: Lise Evans

Graham, wife Jane and Kim Casey. Photo: Lise Evans

It was a young conflict. The average age of the British troops was 25. Jane says: “I think a lot of veterans put the things that happened to them when they were very young in a box and didn’t process it. Years later it’s important that they do process their experiences as it helps to understand what happened and why. It enables them to move on.”

Stratford-upon-Avon Herald

Enter serendipity, when his in-laws passed him a copy of the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald which featured an interview with Kim Casey.

Kim’s adored older brother Petty Officer Air Crewman Ben Casey had died in a helicopter accident during bad weather off Ascension Island. He had been performing manoeuvres alongside his ship HMS Hermes en route to the Falklands. Ben was reported missing presumed drowned.

“Obviously, being on active service has an impact when you look at where you've been and what you've seen. You come back home, but it's not till later on in life that you start mulling things over. But when I saw the piece in the paper, I thought I'd like to meet this lady,” says Graham.

Providence stepped in once more when in the 40th anniversary year, Graham, a Stratford-upon-Avon Boat Club Master, was asked to lay a wreath at the club’s memorial on Remembrance Day. He was told that Kim Casey had been invited to come along too.

“It was just amazing. The first thing I did was to salute her. It was very emotional to meet her, very special,” says Graham. He then gave her an almighty bear hug.

It was a moment of instant understanding between the two strangers. No words were required. It was the first time he’d met a family member of someone who had died in the conflict.

Kim says: “I realised the moment Graham marched up and saluted me on Armistice Day that there was going to be a very special bond and friendship. There was a huge connection."

As reported in the Herald, Kim and partner Steve Welton had just returned from their own pilgrimage to the Falklands in memory of Ben.

She told Graham how the trip had helped her to make sense of what had happened and bring a sense of peace. They could see Graham was struggling and suggested he should consider a trip too.

It was the inspiration he needed. Supported by the Falklands Veterans Charity, Graham and Jane flew out on 17 January and stayed at Liberty Lodge, its accommodation for veterans and their immediate families.

The couple enjoyed an itinerary which featured battleground tours and sightseeing with time for private contemplation.

“There were many bits missing from a very large puzzle that I needed to put together and meeting Kim gave me the incentive to go back. It was very exciting, and I was very nervous about it, but it was what I wanted to do,” Graham says.

Read: Searching for peace after losing Ben

Kim Casey with photos of brother Ben. Photo Mark Williamson

Kim Casey with photos of brother Ben. Photo Mark Williamson

Read: Falklands cove named after fallen brother

Kim Casey and partner Steve Welton at Christ Church Cathedral, Stanley, with the 1982 book of remembrance. Photo: Kim Casey

Kim Casey and partner Steve Welton at Christ Church Cathedral, Stanley with the 1982 book of remembrance. Photo: Kim Casey

Life in the Royal Marines

Graham, who lives in the Warwickshire village of Wellesbourne is originally from Devon. Born in Exeter, he moved to Honiton aged eight along with his two brothers and sister because of his dad’s work.

As part of growing up near the coast he became a lifeguard at Branscombe Beach. Then in 1977 he heard that a commander at the Royal Marines training centre in Lympstone was starting a cadet unit.

He’d been telling his parents he wanted to join the Royal Marines since he was seven, so after discussions with his parents Graham joined.

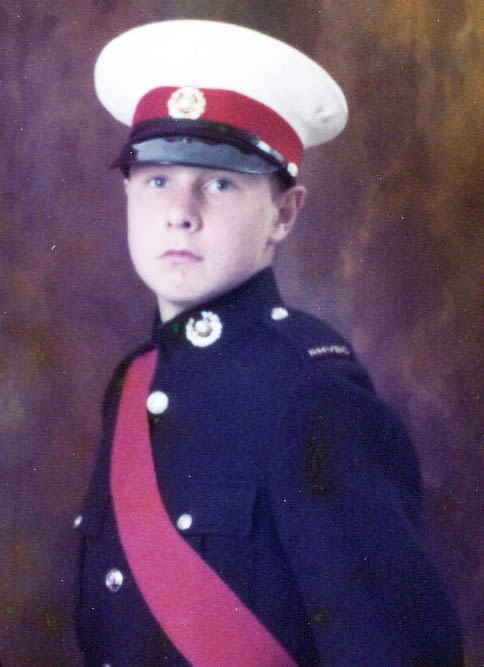

Graham in the Royal Marines Volunteer Cadet Corps, 1978. Photo: Graham Cann

Graham in the Royal Marines Volunteer Cadet Corps, 1978. Photo: Graham Cann

“I wanted to wear that green beret,” he says. Eventually Graham went through the recruitment process and was accepted. “I left school in June, worked in a shop for four months and in October 1979 was put on a train to Lympstone.”

The training, famous for its obstacle courses was “very physical and very demanding,” Graham recalls. “When you look back at the 50 to 60-mile yomp across the island with kit and weapons that 45 Commando did in appalling conditions - that's down to training.”

In September 1980, after completing his 30 weeks of basic training (during which he broke a leg) he went off to join his new unit, 45 Commando based in Arbroath, Scotland. His unit was tasked with being Britain's mountain and Arctic warfare specialists. Graham was deployed to Norway that winter to defend NATO’s northern flank.

Before leaving he was put through his paces with a series of initiation tests by senior, experienced commandos. Fortunately, Graham was under the watchful eye of Ian ‘Frank’ Spencer who age 24, took Graham under his wing.

Falklands invasion

On 2 April 1982, Argentine forces invaded and occupied the British dependent territory of the Falkland Islands. They took the neighbouring island of South Georgia the following day. Neither Britain nor Argentina formally declared a state of war at any point though, so the conflict remained officially an 'undeclared war'.

Three months prior, Graham had been selected to join the Commandos Logistics Regiment so had to leave 45 Commando and comrades he'd spent the last 18 months with. “When it started to kick off, my first part was driving from Plymouth to Kineton and back collecting ammunition to load the ships. I can’t remember how many times, but we were in a four-tonne truck that would only do 45 mph.

“Once we’d finished, we mustered at Stonehouse Barracks, Plymouth, and told we were all moving down to the Falklands. In early May we flew from RAF Brize Norton down to the Ascension Islands. We then sailed south to the Falklands on the transport ship RFA Bedivere on 14 May.

“I had no idea what to expect. Although we were training with live fire onboard ship, the first ‘oh shit’ moment was when we were on the bridge doing submarine watches as we didn’t know what shipping the Argentinians had.”

The Bedivere along with the rest of the task force arrived at Falkland Sound, a sea strait that runs southwest-northeast, separating West and East Falkland.

Graham says: “Once UK forces landed at San Carlos Bay on 21 May unopposed, we rolled in on 23 May. It was done in phases, and we were waiting to off load along with the Canberra, and Norland.”

Battle of San Carlos Water

During the conflict, the horribly exposed stretch of San Carlos Water was a key battleground that became known as Bomb Alley due to repeated attacks from Argentine aircraft on British task force ships.

“We were on a troop carrier ship, but we’ve no armaments. We realised that we were sitting ducks. All I can remember is that there were two Bofor guns on the front.

“Somebody decided to weld machine gun mounts along the side of the ships for our LMGs (light machine guns). That was our defence while we were sat in San Carlos Bay.”

Between 21 and 25 May 1982 three Royal Navy ships were sunk in the area, the HMS Ardent, HMS Antelope and HMS Coventry.

On 23 May Argentine aircraft resumed attacking, striking HMS Antelope, Broadsword, and Yarmouth.

Only Antelope was damaged, sinking before dawn on 24 May, after an unexploded bomb detonated while being defused.

“I can remember going into the Sound late that night when the Antelope got hit and there was an almighty stench.

"I woke up the next morning and I was on the poop deck having a mug of coffee and I saw this red thing, a missile. I thought ‘What the f*** is that?’ And that was it, it all kicked off. In they came…"

The Argentinian jets were flying in at a low level, but the bombs weren’t exploding due to a fuse issue. “The Antelope had an unexploded bomb and when two guys went to diffuse it, it detonated killing the staff sergeant, but the warrant officer survived. These unexploded bombs were a problem.

“On this particular attack one of the bombs hit the mast of the Bedivere, but fortunately bounced and went straight through the front of the ship. We were lucky.

“The drill was if you got a red air raid warning you had to go down to the mess deck – which was below water – so probably three floors down and cover yourself over with a life jacket. I’ve never moved so quickly in all my life.”

Infographic: The Falklands War in numbers

Infographic: The Falklands War in numbers

Ajax Bay

Graham’s role within Commandos Logistics Regiment was the defence of beachhead at Ajax Bay, the singular supply network for the British task force. He lived in a trench for a few weeks and at one stage was extracted with others to a civilian-type ship to guard some very senior Argentinian officers.

During this time the unit was attacked and had to engage in defensive fire. Also in its protection was the field hospital set up in an old slaughterhouse and refrigeration plant. It was nicknamed the ‘red and green life machine’ after the beret colours of the paras and marines. Graham witnessed the many casualties and horrors of war.

Confined at Ajax Bay he wasn’t aware of where his old unit had been deployed and other key elements of the conflict.

“That’s why it was important to go back to the Two Sisters,” he says. "It’s all the more poignant because I had left my old team and that is where I found out Frank had been killed.

There was a colleague in the same troop who came up to me and said, ‘Have you heard the news?’ and I said, ‘What news?’”

Ian 'Frank' Spencer had died on 12 June during operations against enemy forces dug in on the mountain ridge. He was 26. Graham cannot remember how he felt when he heard about his death.

Homecoming

Before he knew it, it was time to go home. He was put on board a ship sailed which around to Stanley. He can't remember which ship. From there he sailed to Ascension Island and was flown back to the UK.

“I can remember one day this Scots Guard came over to me in Ajax Bay and said ‘Royal, you’re going home and I’m here to relieve you. I said ‘really?’. And that was it."

During the war there had been no contact with his family. Yet somehow his brother was there to meet him when he arrived back in the UK. Graham has no recollection of how it was arranged.

“I just don’t know,” he says. “There were no tele-communications, and I can’t remember writing home on blueys.” These are the free pale blue airmail letters used by forces personnel on operational duty.

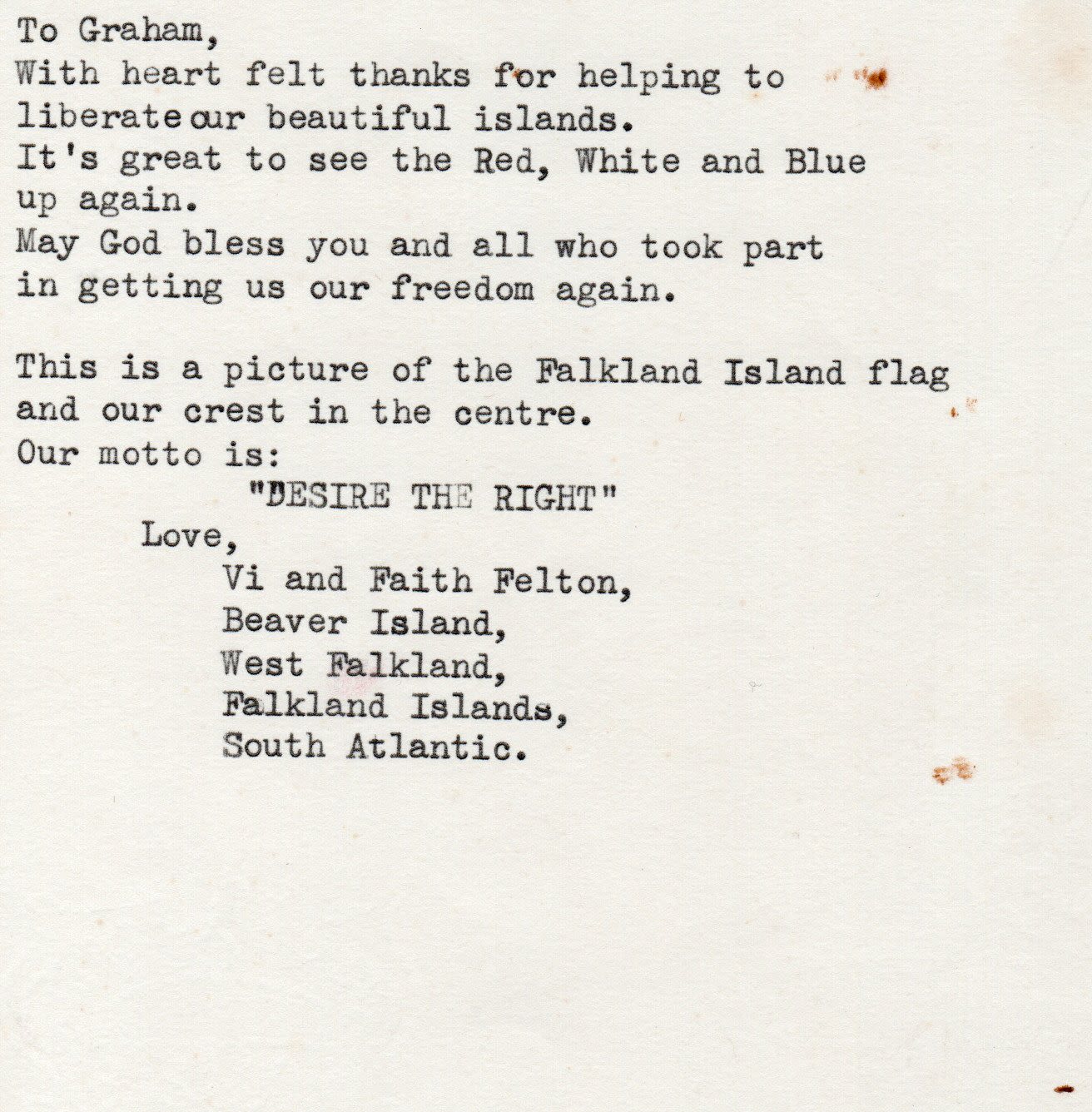

When he got back to Honiton his family put on a ‘welcome home’ party, but Graham can’t remember much about it. He does, however, recall being given a Falklands flag from a mum and daughter who were from the Falkland Islands who happened to be staying in Honiton.

“Nationally there was quite a lot of praise, then it just went into the normal day-to-day stuff. Running a unit, going on exercise, returning to Norway.”

Picture of the Falkland Islands flag given to Graham at his homecoming party. Photo Graham Cann.

Picture of the Falkland Islands flag given to Graham at his homecoming party. Photo Graham Cann.

Life on civvy street

In 2003, Graham finished his service with the Royal Marines and started a job with Warwickshire Ambulance Service, now part of West Midlands Ambulance Service (WMAS). He progressed to the role of head of fleet at WMAS for 10 years.

“The trouble is there was so much guilt because again, I'd left. I've just walked out the gate, left 23 and a half years of friendship, and then Iraq kicks off and Afghanistan. Jane always tells me I’ve done my bit, but you feel guilty.

“I was ready to finish but I guess part of the problem was getting over something that you've loved. Although there is a saying, when you're in you want to be out but when you're out you want to be back in.

“After all those months of training, we used to say it was like they put a cassette in your head – a cassette because it was the 1980s - but they don’t extract the cassette.”

The Falklands 40th Anniversary in 2022 got Graham reflecting. “I think a lot of it was guilt. Luckily, I’d survived, but other people hadn’t. I felt guilty about the pressure it had put on my mum and dad, brothers, and sister. Guilty about the ramifications if anything had happened.

“When I think about Kim and her brother it makes me feel really guilty. Because I came back, and Ben didn’t.”

The connection is that Ben was a Sea King air crewman and would have transported Royal Marines. Graham was at Yeovilton at the same time as Ben and wonders if, when the Sea Kings were on exercise, were they in Norway together.

Survivor guilt

Survivor guilt is a psychological condition that is commonly associated with people who are first on the scene during a crisis. These could be police officers, firefighters and soldiers.

It can also be associated with those who have survived traumatic events or lost people who are close to them.

Survivor guilt exhibits various symptoms based on the reasoning for the trauma caused, often leading to feelings of deep sorrow, disbelief, and occasionally even a sense of accountability.

Survivor remorse is considered a significant symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD.

Professor Dominic Murphy, head of research at veterans' mental health charity, Combat Stress, said: “Survivor guilt describes the difficult thoughts and emotions people can experience when exposed to traumatic events that resulted in the injuries or deaths of others.

“Affected individuals often unfairly judge themselves for not acting how they would have wished, leaving them with overwhelming feelings of guilt and shame.

“Unfortunately, this can cause significant psychological distress that can remain for months, or even years, leading to mental health difficulties such as PTSD.

"Military culture and stigma around military mental health means that those struggling may feel less able to talk about their trauma.

"For some, by the time they do seek help their problems have become much more complex and severe, so it is vital that those affected seek help as soon as possible.”

Graham's service medals from the Royal Marines. Photo: Lise Evans

Graham's service medals from the Royal Marines. Photo: Lise Evans

Falklands re-visited

The couple feel enormously grateful to have gotten the opportunity to visit the Falkland Islands. For Jane it really helped give her an understanding of what Graham went through.

“The key thing is having been there and seen it, I have a better understanding of when Graham talks about his experiences. I can picture it. So when he talks about where his trench was, I can now visualise it. I feel more connected when he’s talking about it.”

The first trip on their schedule was to see all the battlefields and the memorials which Graham says was a humbling experience. “We spent a whole Saturday travelling around east Falkland – it was massive, it was totally unexpected, and it was beautiful, the weather was so lovely, so different to 1982.

“The mention and sight of different mountains, settlements like Goose Green and Darwin. It all helped with the puzzle, putting all these bits together.”

The highlight of the trip was the eight-mile walk in memory of his former Section Corporal Ian 'Frank' Spencer and seven others from 45 Commando who were lost in the attack of Two Sisters.

In doing so they walked in the steps of marines from his former unit who took the same route in 1982.

“I did it with tremendous support from the local volunteers, Terence and Carol Phillips who took us up there,” he says. “They actually followed us in their own 4x4 to ensure we didn’t a break leg.”

45 Royal Marine Commando marches towards Stanley during the Falklands War, 1982. Marine Peter Robinson flies the Union flag. © Crown copyright. IWM (FKD 2028)

45 Royal Marine Commando marches towards Stanley during the Falklands War, 1982. Marine Peter Robinson flies the Union flag. © Crown copyright. IWM (FKD 2028)

He also met up with the daughter of the pair who had gifted him with the Falklands flag back at his homecoming party.

"At the homecoming party, I remember there was a lady and a daughter who presented me with the Falklands flag in a frame with and inscription on the back. I’ve kept it for a number of years and when I realised, I was going back I made enquiries to see if either of them was still alive.”

Inscription on the reverse of the flag presented in July 1982. Photo Graham Cann

Inscription on the reverse of the flag presented in July 1982. Photo Graham Cann

The answer was affirmative, and a reunion duly arranged with Faith Felton and her son. Graham says: “I couldn’t work out why they were in Honiton in Devon, and it transpired her grandfather had been medically evacuated due to heart problems and her aunt happened to be living in Honiton.

“Faith was going to the same school as my sister and that’s how they came to be there. It was wonderful to meet her again, quite a meeting. They were really thankful which is sometimes hard to accept.”

Is Graham glad he returned? “Absolutely. One hundred percent. It’s one of the best things I’ve done,” he says. He’s already planning a return journey but not sure when yet.

“I feel very fortunate that it is a place where we are able to return, whereas in other conflicts like Afghanistan, people can’t go back. I am quite privileged to be in that position. It’s meant a hell of a lot to show Jane too, so she has a better understanding.

“It was a great experience to see what a beautiful place it is. You would have thought that the beaches where we saw the penguins were in the Caribbean - stunning.”

Jane adds: “Now we have memories of being there together, of the people we met and the places we visited. It is such an amazing, peaceful place. It’s the only way you can explain it. Everyone is so friendly and there is a real sense of community.

“We have created a layer of new memories. Now, when we talk about the Falklands, we aren’t just talking about the war, we are talking about the time we went and the new people we met.

“It’s about piecing together all the bits and putting things to rest. Understanding what happened because he saw it as a 19-year-old marine and there was a lot more stuff going on at the same time. I think it has helped him see that bigger picture and what part he played.”

Graham and Jane outside Liberty Lodge, near Stanley. Photo: Graham Cann

Graham and Jane outside Liberty Lodge, near Stanley. Photo: Graham Cann

Welcome to the Falkland Islands, Mount Pleasant Air Terminal. Photo Graham Cann

Welcome to the Falkland Islands, Mount Pleasant Air Terminal. Photo Graham Cann

Teal Inlet, East Falkland. Photo: Graham Cann

Teal Inlet, East Falkland. Photo: Graham Cann

Main Falklands War memorial, Stanley.

Main Falklands War memorial, Stanley.

Jane and Graham outside Government House, Stanley, the home of the Falkland Islands' governors since the mid-19th century. Photo: Graham Cann

Jane and Graham outside Government House, Stanley, the home of the Falkland Islands' governors since the mid-19th century. Photo: Graham Cann

View of San Carlos Water, East Falkland. Photo Graham Cann

View of San Carlos Water, East Falkland. Photo Graham Cann

San Carlos War Memorial. Photo Graham Cann

San Carlos War Memorial. Photo Graham Cann

Two Sisters yomp with Falklands veteran Paul Musgrove, former lieutenant colonel with 29 Commando Royal Artillery.

Plaque at Moody Brook, East Falkland. Photo: Graham Cann

Two Sisters mountain ridge, East Falkland. The scene of the Battle of Two Sisters in June 1982. Photo: Graham Cann

Two Sisters mountain ridge, East Falkland. The scene of the Battle of Two Sisters in June 1982. Photo: Graham Cann

On the track to Stanley from Two Sisters. Photo: Graham Cann

King penguin colony at Volunteer Point, East Falklands. Photo: Graham Cann

Looking forwards

After finally meeting Kim, Graham felt strongly that it was his duty to look after her. “He’s found a bond with Kim as he has a younger sister too. He’s thinking about Kim’s loss and also Ben’s. Ben lost his life, so he needs to look out for her,” says Jane.

“Meeting her was quite a turning point as it was an opportunity to talk more about what happened and coincided with the 40th anniversary. Going back was another step in that.”

Since the initial meeting at the boat club, the pair and respective partners have celebrated birthdays, a wedding anniversary and commemorated the war dead at the National Arboretum.

“She is like a sister to me now," Graham says. "It feels like I've always known her."

“It’s all part of a jigsaw,” adds Kim. “That class of ’82 has many different parts – Graham was a serviceman and I lost my brother – but we are all part of that same family.

“He has become the brother I no longer have.”

Kim and Graham outside Stratford-upon-Avon Boat Club. Photo: Lise Evans

Kim and Graham outside Stratford-upon-Avon Boat Club. Photo: Lise Evans

Combat Stress

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this story, confidential advice support and advice is available from the Combat Stress 24-hour Helpline on 0800 138 1619.

Get in touch

If you have any comments or feedback on the story please get in touch at hello@morethanpr.co.uk